In 10 seconds? Increasing and restoring whale populations could help fight climate change and conservation. A recent (2022) paper has added to the research evidence about whales’ carbon capture potential.

What’s the story? It’s no news that our oceans sequester the most CO2 from the atmosphere – a whopping 40 percent – but the role of whales has not received enough attention so far. A recent paper used a 2019 IMF report (more below) as a launchpad to investigate whales’ contributions to carbon sequestering but was critical of the IMF's optimistic estimate of a whale's value.

OK, what does the IMF report say? The paper by International Monetary Fund economists and scientists estimated that each whale on the planet was worth 2 million dollars, and the total population was valued at over a trillion greenbacks – because of their green credentials. Their message at the time was: protecting whales pays by limiting greenhouse gas emissions and helping us work towards climate targets.

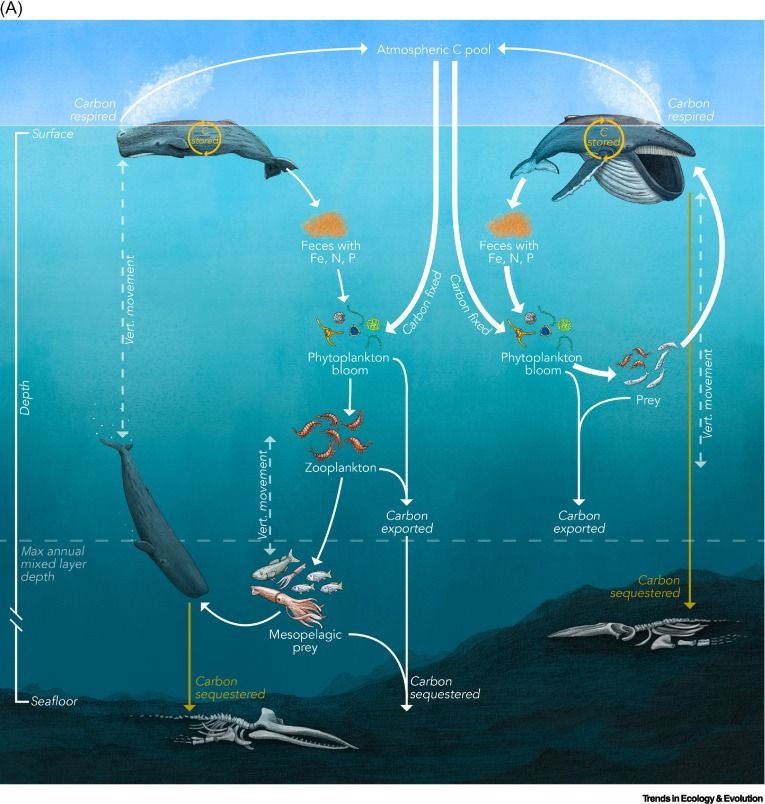

That’s just a load of… what could whales possibly do for the climate? Mind your language, although you might be right! Whales release their liquid waste and fertilize the upper layers of the oceans. It is exactly what phytoplankton, the tiny organism, AKA the biggest carbon sequester on the planet, needs! Additionally, when whales die, around 33 tons of CO2 captured during their lives sink with them to the bottom of the ocean. That’s 33 million tons if we count the current population – according to the IMF paper.

So, how does carbon capture work? Scientists noticed that areas with large numbers of whales are where phytoplankton blooms. This is because due to their diet of squids and other marine life, the big mammals pump out feces full of nutrients, including iron. Phytoplankton captures via photosynthesis around 40% or 37 billion tons of CO2 yearly. That's four times more than what the Amazon region takes out of the air, so whales play a vital role in natural carbon sequestration. Scientists estimate that a small, 1% increase in phytoplankton productivity would equal 2 billion mature trees in terms of offsetting CO2.

But you said the new research was critical of this data? Yes, the researchers said that the current estimates did not include all the direct and indirect ways whales captured carbon. One reason was that they did not include sperm whales and only included the Southern Oceans. On the other hand, they critiqued the $2 million value put on each whale, mentioning that no empirical data was backing up their work to increase phytoplankton productivity by 1%. They also noted that ‘real’ carbon storage means decades in terms of time and means carbon taken to the depth of the oceans. Phytoplankton and zooplankton don’t do this.

How did researchers find out about whales’ carbon storage potential? Science was not always on the whales' side. Initially, the thinking was that they were net contributors to atmospheric CO2 levels. This was before scientists turned their attention to their relationship with phytoplankton. Researchers have come up with a ratio of carbon exported to the depth of the sea vs iron added to the upper levels by the whales that stimulate phytoplankton growth. For this, they established the average amount of iron whales consume through their diet and also how much they release back into the water – which is as much as 90 percent!

But it sounds like researchers are contradicting each other here? Well, the debate is more about the methods, models, and estimates. Both economists and conservationists say we need to help whale populations grow and that they can help capture more carbon. The question is to what extent? The recent paper concluded that there were still many unknowns preventing us to come up with a viable calculation about a whale’s carbon capture and sequestration potential. Only when we will fill the missing gaps, can policymakers decide to include whale conservation in climate strategies.

What can be done to protect and increase whale populations? Commercial whaling was drastically restricted during the last few decades, but the number of whales is a mere 25% of what it was before. Collisions with ships, entanglement in fishing nets, and swallowing plastic bags are major causes of their early deaths. Economists suggest financially compensating industries to increase whale protection. For example, shipping companies should be paid to alter routes and limit fatal collisions. Fleets should be made less noisy, to interfere less with the long-distance voice communication of whales.

Great whales are massive carbon sinks

Blue whales are the biggest among 90 or so living species and the largest animals on Earth. Up to 30 meters long, they can weigh over 170 tonnes. These mammals are particularly good at storing carbon due to their size. They feed on as much as 35,000 kg of krill – tiny shrimp each day. For this, they dive to 500 meters under the surface of the ocean.

They were subject to intensive whaling during the 20th century, which pushed them to the brink of extinction. Current estimates put their numbers between 10,000-25,000 whereas the total number of whales dropped from 4-5 million to around 1 million today.

Blue whales communicate with each other via sound and in ideal conditions can hear their peers from 1,600 km.

Endre has distilled 6 research articles saving you 21 hours of reading time.